In the world of

black and white,

there is . . .

Columns

Hairy

Gravy

What's The Use Of Getting Sober?![]()

Reviews

Original Material

An

Interview with Will Eisner

An

Interview with Will Eisner

-by

Barry Wolborsky

Will

Eisner is one of those rare comic book professionals who has attained the status

of living legend, with a career spanning more than sixty years. He is the

creator of "The Spirit" comic strip and inventor of the modern graphic

novel. In addition, he is an educator who has written books on his craft and

taught Sequential Art at New York's School for Visual Arts. As if these

accomplishments weren't enough, his name is eponymous with an award thought by

many to be the highest honor a comic book professional can receive - The Will

Eisner Comic Industry Award.

Mr.

Eisner was kind enough to take the time out of his busy schedule for a phone

interview, which I found to be an enjoyable and enlightening experience. Some of

the topics we touched upon are his early influences, thoughts on the current

state of the industry and the literary philosophy that is reflected throughout

his work.

Gray Haven: You're

considered to be one of the most influential creators in the comic book medium.

Who have been the biggest influences on your art and storytelling, and why?

Will

Eisner: Well, certainly early on, my influences were cartoonists; Milton Canniff,

from whom I learned how to tell stories. George Herriman, who did "Krazy

Kat," influenced my ability to engage a reader dramatically. The third

cartoonist who was very influential, was strangely enough, Elzie Segar, who did

"Popeye," who taught me how to achieve humor and action merely with

postures. Anybody looking at Popeye realized that he never jumped around the way

Spider-Man does, yet he was very active. He was seen as a very, very violent and

active man. Those three men were very influential.

And

as far as writing is concerned, the storytelling, people who really influenced

me were the short story writers of the 30's, in the pulp magazines I grew up on.

I just doted on those. There's O. Henry, Ring Lardner, Saki, the French short

story writer, Guy de Maupassant. The short story dominated popular

literature of that era.

GH: Some of your graphic

novels focus on religion, specifically Judaism, and life in the big city,

specifically New York City. What about these two subjects do you find so

appealing?

WE:

Well, it has to do with my attitude, my literary philosophy; I believe that

people are concerned with life. The enemy is not people, the enemy is life

itself. That struggle is a constant interest. When we think of enemies we think

of people, we think of villains, but these are only temporary, they're surface

things. Underlying it all is survival.

Now

the reason for my interest in city life is because the city is one big theater,

it's where it all happens; it's where conflict occurs. It's where the greatest

interaction between people occurs. Actually, in the beginning of our

civilization, the jungle was the place of great danger and people retreated to

the city for safety. As time wore on we conquered the jungles, and now the city

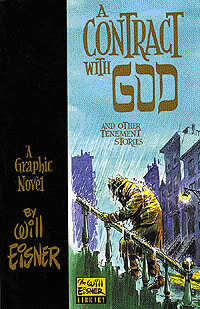

has become the place of danger. As far as religion is concerned, my

only discussion on religion was my first book, "A Contract With God."

There I tried to undertake a subject that I felt was more mature and more

significant than anything comics had attempted. Up to that point comic books and

the comic medium never really engaged a subject that was so universally

important to everybody.

GH:

Why do you think "The Spirit" remains so influential 60 years after

its debut?

WE:

Well, I'm just as surprised as anybody else. I guess the only answer I can give

to that was something that was told to me by one of my students one day. He said

the Spirit was very much like Sherlock Holmes in dealing in fundamental stories.

Stories like that endure, just as the great short story classics have endured.

GH: To me the Spirit is

just a guy in a suit and hat, which could really be anybody.

WE:

That's right. He was never intended as a superhero. Sometimes people think that

because he's wearing a mask, he's a superhero, but I never intended him as a

superhero. As a matter of fact, one thing that should be noted here is that

"The Spirit" was not written for a comic book audience. "The

Spirit" was written for a newspaper audience for adults.

GH:

Do you have any favorite works of your own that stand out?

WE:

Well, my favorite one is always the last one I did (laughs). But "A

Contract With God" is still important to me. And the one that was

personally enjoyable was the one I did recently called "Minor

Miracles," which came out this year. It was fun to do.

GH:

I heard the lines for your table were quite long at this year's small Press Expo

in Bethesda, MD.

WE:

That was great. I was awed by that. I was so delighted because these are all

young people on their way up. They have in their hands the future of our

profession.

GH: You must be pretty

excited about the resurgence in your popularity.

WE:

Oh yeah, well, obviously (laughs). It's a little unnerving to me to tell you the

truth. I aspired to be a promising young cartoonist. I'm ending up as a

promising old cartoonist.

GH: Some of your most

recent projects such as "A Day in Vietnam" and "Minor

Miracles" contain the adult subject matter that has been customary in your

graphic novels, yet your 4 color graphic novels "The Princess and the

Frog" and "Don Quixote" seemed aimed at an all ages audience,

specifically children.

WE:

They were actually experiments with television and literacy. "Princess and

the Frog," "Don Quixote" and "Moby Dick," which is

coming out in the spring, were the result of an experiment that I worked on with

Public Television about 5 years ago to develop a series of films on television

that would help them develop a reading experience on television. This was at the

peak of national interest in advancing literacy. So I reduced a couple of

classics into a film. Actually a

series of stills that had limited animation designed for TV. These are simply

adaptations, and really an introduction to the classic. I couldn't resist

altering it somewhat. For example, in the case of the "Princess and the

Frog," I was astounded when I read the original Grimm story fairy tale, to

find she was really a rather bitchy lady (laughs). When I grew up I always

thought that she was a kind and sweet and lovely girl. So I had fun with that.

And then in "Don Quixote," as I did the story I realized that most of

us working in this field are really Don Quixotes. We're all dreaming of

ourselves beyond how the public sees us, and so I thought I would expand the

thought, go a little bit beyond the story itself, make it a kind of a

philosophical lesson. That's the reason I had Cervantes in the end come back and

beknight Don Quixote.

GH:

I know that many of your longtime fans enjoyed it. Did you get any kind of

positive reaction from any of the kids that read it or their parents?

WE:

I actually I got positive reaction from parents, which pleased me. But really, I

wasn't really writing to children. It's very hard for me to write to children. I

write to a 50 or 60 year old guy who just lost or had his wallet stolen on the

subway (laughs) and he's wondering "Why me, God, why me?"

GH: Some of your books are

semi-autobiographical, such as "To the Heart of the Storm" or

"The Dreamer." How much of those books are autobiographical and how

much are fictionalized?

WE:

"The Heart of the Storm" was totally biographical, and very true,

actually everything that happened. I only changed the names and the places,

didn’t fabricate any events, it all just happened as I told it.

GH: So "The

Dreamer" is your book of advice to cartoonists trying to break into the

field?

WE:

It's to say to the kids who are growing up and going out into the field,

"Look it's always been this way and if you stay with it, and remain the

dreamer that you really are, you'll prevail."

GH: What are your thoughts

on the current state of the industry, especially since there's been so much talk

of the market being in a depressed state and comics dying?

WE:

Well, look, the industry, the market is depressed, there's no question about

that. Comic book stores are slowly declining in quantity. But the medium itself

is more mature and better than it has ever been.

GH: The graphic novel has

become more popular than ever before, which I think is a great thing.

WE:

It's one of the most reassuring things that have happened to me in years.

GH:

What do you think will save the industry?

WE:

I think what'll save the industry are the artists themselves. In answer to

"When will 'they' ever recognize us," the answer is, "They will

recognize us when we produce recognizable material." It's the content.

There is no way of legislating approval.

GH: Do you think that

superheroes, and the fact that they're so prevalent, are what are preventing

that approval?

WE:

Well, in a way. The problem is not superheroes…it’s how they’re presented.

Trash and pandering in any field, whether it's in movies, whether it's in

literature, always have the effect of turning people from a medium. Most folks

are really not aware of the fact that below that 90% of trash there is some 5 or

10 percent of really good stuff that they should look for.

GH: Have you read any

recent works such as Chris Ware's "Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on

Earth" or Judd Winick's "Pedro and Me"?

WE:

Yes, I've seen those, they're good, they're very good, and they're very

promising, very interesting. They are pushing the envelope.

GH:

Are there any upcoming projects that you can tell us about?

WE:

I'm working on a book now, but it's been my practice not to talk about a book

while I'm in the middle of it, because it kind of dilutes itself when I do.

GH: Are there any projects

outside of cartooning and comics that you would like to take on, such as movies

or television?

WE:

No, I'm really curiously not interested in film at all. I couldn't care less of

whether a film is made of my book or work.

GH: I notice that your web

site, WillEisner.com, is still under construction. Any time frame as to when

it'll be up and running?

WE:

Yes, the two people who have been working on it have been on it for 6-8 months

now. What happened is they have a day job, and it eats them up, so they can only

spend a few hours a day on this thing. But it'll probably get up and going

pretty soon.

GH:

With so many important contributions to the comics field, what would you

consider to be your greatest legacy?

WE:

My contribution to the validity of comics as a valid literary form.

Copyright©2000 Barry Wolborsky